This double-arched bridge spans State Route 96, near milepost 438, of the Natchez Trace Parkway. The bridge, located roughly 8.7 miles south of the northern terminus of the Parkway, is 1,572 feet long, 37 feet wide, rises 145 feet above the highway underneath, and has no less than 107 feet of clearance below. The symmetrical northern arch is 582 feet long while the asymmetrical southern arch is 462 feet in length.

An interesting characteristic of the bridge is that there are no spandrel columns or other means to transmit the load of the bridge across the entire span of the arch. Instead, the weight of the bridge is concentrated at the top of each arch. This design feature, by Florida-based Figg Engineering Group, gives the bridge its unique, uncluttered, and very clean lines.

This bridge was the first segmentally-constructed concrete arch bridge in the United States. The arches are made of 122 hollow box pre-cast segments. Each segment is 9.8 feet long and weighs between 29 and 45 tons. The bridge deck is made of 196 pre-cast, post-tensioned trapezoidal box girder segments roughly 8.5 feet long. Where the bridge rests on the arch, the concrete is 13 feet deep. All of the concrete, except that for the foundations and piers was cast off-site and then assembled to build the bridge. It was constructed using the balanced cantilever method to minimize potential environmental damage.

The bridge cost $11.3 million to build and was completed in October, 1993. It was opened to traffic on March 22, 1994. The Eleventh International Bridge Conference named it the single most outstanding achievement in the bridge industry for 1994. It earned the Presidential Award for Design Excellence in 1995 and the Federal Highway Administration Award of Merit in 1996.

If you get a chance, please take a moment to look at how such a modern-looking bridge fits into the landscape and manages to blend in with the historical feeling of the Natchez Parkway. Views from the southeast and northwest are available and quite remarkable.

Flower in the Snow

This photo was taken in the height of summer. The information on the original image shows a creation date of July 10th. Based on the snow still on the ground, anyone would be hard-pressed to know the time of year from simply looking at the photo. The only hint that the picture wasn’t taken in winter is the fact that the flower is in bloom.

The location of the image was at an elevation of 12,000-feet (+/- ) in the heart of Rocky Mountain National Park, technically part of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The air was crisp and the wind was blowing as I took photos above the tree line in a pair of shorts and a light, short-sleeved shirt. Most of the other people there at the time displayed far more sense than I did and were bundled in multiple layers of clothing to stay warm. Several gave me some very strange looks as I walked around, camera in hand, and took a number of photos. Some remarked that I was oblivious to the cold temperature, but I made a point to go back inside a Visitor Center to get warm before I continued my journey. You’d be surprised how quickly you can take photos when you’re not really dressed for the cold, I mean, invigorating, conditions! The warmth of the Alpine Visitor Center never felt so good!

Rocky Mountain National Park contained 385.5 square miles, originally part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, when it came into existence on January 26, 1915. The Never Summer Range was not included in the 1915 law, but was subsequently added in 1929. In 1990, the park grew to its current size with the inclusion of 465 acres around the Lily Lake area. On October 26, 1976, the park became an International Biosphere Reserve. Today, the park contains roughly 416 square miles or 265,769 acres. The park also licensed the nation’s first female nature guides, sisters Ester and Elizabeth Burnell, in 1917.

Rocky Mountain National Park has some of the most spectacular and scenic views you can imagine. 72 mountains thrust skyward to a height of 12,000-feet or more. The highest peak, Longs Peak, rises to a height of 14,259-feet. The mountain is visible from nearly everywhere in the park and was named for Major Stephen H Long who led a government-sponsored scientific expedition into the area in the summer of 1820. Ironically, he was never closer than 40 miles to the peak that bears his name.

Trail Ridge Road, the highest paved road in any US national park, provides truly breathtaking views of the area as it soars to an elevation of 12,183-feet. When the weather cooperates, the landscape stretches out all around you in a 360-degree panorama that you will never forget. I felt as if I were standing on top of the world!

The park has 359 miles of established hiking trails that range from easy to difficult with 260 miles of horse trails. The park also boasts 5 visitor centers, 60 types of mammals (including moose, elk, bighorn sheep, black bears, coyotes, and mule deer), 280 species of birds, 900 different plants, 150 lakes, and 476 miles of streams and creeks, including the headwaters of the Colorado River.

If you visit Rocky Mountain National Park, remember to acclimate to the area before engaging in strenuous activity. No part of the park is lower than approximately 7,500 feet, or roughly 2,500 feet higher than the self-proclaimed Mile High City of Denver. At high elevations, altitude sickness is a manageable nuisance. The weather can, and does, change quickly. The day may start out bright and sunny and turn into a last-season snowstorm before nightfall. In 2012, the most recent data at the time of this post, the coldest temperature inside the Alpine Visitor Center, at 11,798-feet, was 21.2 degrees Fahrenheit. Several yards of snow drifts insulate the building from much colder temperatures when it is closed for the winter.

I discovered this old barn while on a motorcycle ride. When I saw it, I pulled to the shoulder of the two-lane road, took off my helmet, and studied the interplay of the light, shadow, color, and texture on the structure for several minutes. I’m not sure what it was, but something about that old barn captivated me. I made a mental note to bring my camera with me and take a picture of it the next time I passed by it. Much to my chagrin, I soon learned that I should have made a written note rather than keeping the pledge solely in my head.

Between Murphy’s Law and my routinely forgetting a promise I made to myself, it took several trips by this local landmark before everything came together for this photo. The image was captured in mid-morning on a quite warm late spring/early summer day. The green grasses from the spring rains were about to turn brown under the summer sun.

This image has been shown in a number of galleries and usually 9 out of 10 people are surprised to learn that it was taken in northern California. This image represents a California that few people know even exists. Many think that the Golden State is nothing but sun and surf or one huge megalopolis with nothing but millions upon millions of people driving on 8- or 10-lane highways in a 24/7 frenzy to get someplace else. While there are parts of the state that reflect that stereotype, there are other parts of the state that seem to be a world away. It is in these locations that one can get a sense of what California might have looked and sounded like before over 30 million people called it home. Roughly 1/10th of the nation’s total population lives in just this one state. The monetary output of the state, as measured by GDP, easily ranks it annually in the top ten economies of the nations of the world.

When I took this picture, I heard birds singing. Horses whinnied in the distance. A light breeze caused the leaves to flutter and rustle slightly. The tall grasses swayed gently to the breeze. A car would pass by, occasionally. The sound it made in its transit would quickly fade away and be replaced by the same sounds that have echoed through the area for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. For a few, brief moments, I stepped back in time. I enjoyed every minute of it!

Yellowstone National Park

This picture was taken in late April. Clearly, winter still had a grip on Yellowstone. For the next week, I roamed around the area and took literally thousands of photos. One of these days, I’ll get around to picking out a few of the better ones and putting them on this website. During my stay in Yellowstone, the snow was high, the sky was clear, the roads were mostly passable, and the tourists were sparse. It was a great time to see all the wonders the park had to offer.

Yellowstone National Park was created in 1872 by the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act which says, “the headwaters of the Yellowstone River…is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale…and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

The park itself is huge, covering 3,472 square miles (8,987 square kilometers) or 2,221,766 acres or 899,139 hectares. To put that into perspective, the size of the park is larger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware, combined. The park is 63 air miles or 102 km from north to south and 54 air miles or 87 km from east to west. 96% of the park is in Wyoming, 3% in Montana, and 1% in Idaho. The highest point is Eagle Peak at 11,358 feet and the lowest point is Reese Creek at 5,282 feet. The continental divide bisects the park north to south. The surface area of the park is 5% water, 15% grasslands, and 80% forests. Yellowstone National Park has 5 entrances with 466 miles of road of which 310 miles are paved. It also has more than 15 miles of boardwalk to protect visitors from the heat generated by the volcanic hot spot that provides the energy to fuel more than half the world’s geysers. There are roughly 1,000 miles of trails, 92 trail heads, and 301 back-country campsites.

Yellowstone Lake, the largest water feature in the park, has a surface area of 131.7 square miles and boasts 141 miles of shoreline. The lake is 20 miles long north to south and 14 miles long east to west. The average depth of the lake is 140 feet. The maximum depth of the lake is 410 feet.

Yellowstone National Park owes much of its uniqueness to the fact that it is an active super volcano. The eruption that created the park occurred roughly 640,000 years ago and produced an ash cloud estimated to be 2,500 times the size produced by the 1980 eruption of Mt. Saint Helens in Washington. According to the USGS, the recent rise in the floor of the caldera as slowly significantly since January, 2010. The caldera in the park is one of the world’s largest and measures 45 x 30 miles across. The park has 1,000-3,000 earthquakes annually, more than 10,000 hydrothermal features, over 300 active geysers, and 290 waterfalls. Yellowstone is truly a special place.

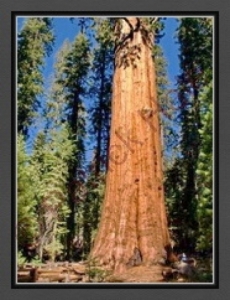

The General Sherman Redwood, located in Sequoia National Park. is the largest, by volume, tree in the world. In the photo of the tree shown here, if you look to the right of the base of the tree, you’ll see a person. That gives you an idea of the overwhelming massiveness of the tree.

Computing the volume of a standing tree is the practical equivalent of calculating the volume of an irregular cone. For purposes of volume comparison, only the trunk of a giant sequoia is measured, including the restored volume of basal fire scars. The additional wood found in the branches of the tree is not part of the calculation. Using these accepted standards and actual field measurements taken in 1975, the volume of the Sherman Tree was calculated to be slightly over 52,500 cubic feet (1,486.6 cubic meters).

Standing next to this enormous redwood is nothing short of awe-inspiring. The photo here doesn’t capture the massive nature of the tree when you gaze upon it or turn your gaze skyward and look up the trunk. To say that it is huge is an understatement of gigantic proportions. When you remember it is is alive, it becomes even more amazing. If you ever get the chance to see this tree, or any of the trees listed below, please take a moment to look at them. You will never forget it!

Here are some facts about this tree that I thought you might find interesting.

|

Characteristic |

Feet |

Meters |

| Height |

274.9 |

83.8 |

| Circumference at Ground |

102.6 |

31.1 |

| Maximum Diameter at Base |

36.5 |

11.1 |

| Diameter 60′ (18.3 m) above base |

17.5 |

5.3 |

| Diameter 180′ (54.9 m) above base |

14.0 |

4.3 |

| Diameter of Largest Branch |

6.8 |

2.1 |

| Height of First Large Branch above the Base |

130.0 |

39.6 |

| Average Crown Spread |

106.5 |

32.5 |

As an additional bit of information, here’s a list of the largest giant sequoias known to exist.

|

TREE NAME |

LOCATION |

HEIGHT (Feet) |

CIRCUMFERENCE (Feet) |

VOLUME (Cubic feet) |

||

|

1. |

General Sherman |

Giant Forest |

274.9 |

102.6 |

52,508 |

|

|

2. |

Washington |

Giant Forest |

254.7 |

101.1 |

47,850 |

|

|

3. |

General Grant |

Grant Grove |

268.1 |

107.5 |

46,608 |

|

|

4. |

President |

Giant Forest |

240.9 |

93.0 |

45,148 |

|

|

5. |

Lincoln |

Giant Forest |

255.8 |

98.3 |

44,471 |

|

|

6. |

Stagg |

Alder Creek |

243.0 |

109.0 |

42,557 |

|

|

7. |

Boole |

Converse Basin |

268.8 |

113.0 |

42,472 |

|

|

8. |

Genesis |

Mountain Home |

253.0 |

85.3 |

41,897 |

|

|

9. |

Franklin (near Washington) |

Giant Forest |

223.8 |

94.8 |

41,280 |

|

|

10. |

King Arthur |

Garfield |

270.3 |

104.2 |

40,656 |

|

|

11. |

Monroe (near Auto Log) |

Giant Forest |

247.8 |

91.3 |

40,104 |

|

|

12. |

Robert E. Lee |

Grant Grove |

254.7 |

88.3 |

40,102 |

|

|

13. |

John Adams (near Cattle Cabin) |

Giant Forest |

250.6 |

83.3 |

38,956 |

|

|

14. |

Ishi Giant |

Kennedy |

248.1 |

105.1 |

38,156 |

|

|

15. |

Not Named (near Pershing) |

Giant Forest |

243.8 |

93.0 |

37,295 |

|

|

16. |

Summit |

Mountain Home |

244.0 |

82.2 |

36,600 |

|

|

17. |

Euclid |

Mountain Home |

272.7 |

83.4 |

36,122 |

|

|

18. |

Washington |

Mariposa Grove |

236.0 |

95.7 |

35,901 |

|

|

19. |

Pershing |

Giant Forest |

246.0 |

91.2 |

35,855 |

|

|

20. |

Diamond |

Atwell |

286.0 |

95.3 |

35,292 |

|

|

21. |

Adam |

Mountain Home |

247.4 |

94.2 |

35,017 |

|

|

22. |

Roosevelt or False Hart |

Redwood Mountain |

260.0 |

80.0 |

35,013 |

|

|

23. |

Nelder |

Nelder |

266.2 |

90.0 |

34,993 |

|

|

24. |

AD |

Atwell |

242.4 |

99.0 |

34,706 |

|

|

25. |

Hart |

Redwood Mountain |

277.9 |

75.3 |

34,407 |

|

|

26. |

Grizzly Giant |

Mariposa Grove |

209.0 |

92.5 |

34,005 |

|

|

27. |

Chief Sequoyah |

Giant Forest |

228.2 |

90.4 |

33,608 |

|

|

28. |

Methuselah |

Mountain Home |

207.8 |

95.8 |

32,897 |

|

|

29. |

Great Goshawk |

Freeman Creek |

255.2 |

90.2 |

32,783 |

|

|

30. |

Hamilton |

Giant Forest |

238.5 |

82.6 |

32,783 |

|

| The information presented here is courtesy of the National Park Service. | ||||||

This photo is an example of being in the right place, at the right time, and taking advantage of an opportunity when it comes along. I was trying to take a picture of a woodpecker. (Yes, I know the difference between woodpeckers and squirrels, on a good day. The picture I was trying to take is elsewhere on this page.) I could hear the woodpecker hammering away on a tree, but every time I thought I had him cornered, he’d fly to another tree. As I scanned and searched the trees to find him, I saw this squirrel leisurely and contentedly sunning himself in the warm afternoon sun. I couldn’t resist the image as it captured the feeling of the lazy, spring afternoon that I apparently shared with the squirrel.

This heron was very skittish and as camera shy as could be. Over several days, I tried multiple times, without success, to get a good picture of him. One morning, just after daybreak, I took my camera with me as nothing more than an after-thought. When I approached the lake, I captured this image of him as he waded in shallow water looking for his breakfast. The light wasn’t the best, so I opened the lens to let in as much of the ambient light as possible. The reflections of the dormant trees in the still waters enhanced this photo by giving it context and character. Shortly after this picture was taken, he flew away and made a raucous noise as he left. I don’t speak Heron, but he didn’t sound at all happy.

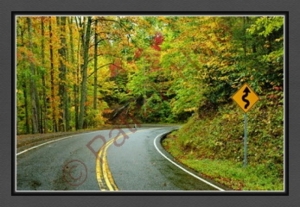

Before I took this picture, the weather had been miserable all day and was highlighted with lots and lots of rain. The skies were still dark with a foreboding sense to them and the inclement weather was still at hand. The saving grace to an otherwise dreary day was that the traffic was light and it was easy to take this photo to capture the fall colors in the Appalachian Mountains. I used a high ISO to make the most of the limited light and get as much of it into the lens as I could, did my best to keep my equipment dry, composed the photo, and pressed the shutter release. A few moments later, the rain picked back up, I put my camera gear away, and continued my travels.

In short order, two more squirrels came out to enjoy the warmth of the sunshine. None of them seemed to be bothered in the slightest by my presence. While the squirrel in the middle nods off, the other two keep an eye out for anything moving in the area. All three of them took turns sleeping as they lounged lazily in the sun for a while. Then they disappeared just as quickly as they first appeared. I can only guess that they returned to doing whatever squirrels do on a lazy, sunny, spring afternoon.

Great Blue Heron in House Reflection

Great Blue Heron in House Reflection

This image was captured early on a very cold morning just after the sun crested the eastern horizon. The temperature was in the low 20s with a wind chill in the mid-teens. Around the sides of the lake, a thin ring of ice had formed overnight. This heron stood alert and ready to find its morning meal in water that was barely above freezing. He pulled in his long neck to help retain body heat and let the sun’s early rays warm him in their golden glow. He stood there for several minutes while I took off my gloves and pulled the camera out from under my jacket. Had it been warmer, I’m not sure he would have allowed me to get ready as long as he did without flying away. Needless to say, I took this picture and it captured the moment in the life of a heron on a cold, crisp, half-frozen morning. I wouldn’t have been able to stand in that cold water in my bare feet without complaint nearly as long as he did!

This photo was taken in the early morning. The bright spot in the lower right of the frame is actually the sun peeking over the mountains. The temperature was in the high 20s or low 30s and the wind was picking up. The weather was supposed to be warmer and with only a slight breeze. There was some discussion of keeping the hot air balloons on the ground, but the decision was made to launch them before the wind got any worse. This photo captures the feelings I had at the event. It was a raw, dreary, cold day and the wind seemed to bite right through my multiple layers of clothing. The clouds from an approaching cold front, which would leave roughly 8 inches of snow in its wake, increased as the day wore on. The grayness of the day, despite this being a color photo, is captured in this stark picture. The silhouettes of the hot air balloons drive home the fact that the rising sun was about to be hidden by the clouds. Between pictures, I put my camera under my jacket to try to keep it warm. I was only marginally successful. This event produced some very colorful photos later in the day, when the weather improved for a few, brief moments, but this image reflects the mood I felt as I battled the elements to memorialize the hot air balloons as they struggled into the cold, cloudy sky.

Gathering Storm and The Road Just Traveled were literally taken within seconds of each other. Gathering Storm is the view to the west while The Road Just Traveled looks east. I took the first photo, turned around to get back into my car, and took the second picture. They were taken on US Highway 64 between Taos and Tres Piedras, New Mexico. The storm started with rain and turned to snow in the Carson National Forest from Tres Piedras to Tierra Amarilla. My final destination for the day was Chama. I wanted to ride the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad the roughly 64 miles from Chama, NM (7,875 feet) to Antonito, CO (7,890 feet) via Cumbres Pass (10,015 feet), the loftiest point traversed by a US passenger train. The Cumbres & Toltec is the highest and longest coal-fired, steam-powered, narrow-gauge railroad in the United States. Upon arrving in Chama, the entire town was without electricity due to the storm that had just swept through the southern Rockies. Everyone I met was friendly and extremely helpful which made the loss of power more amusing than anything else. Until it wasn’t available, albeit briefly, I didn’t realize just how much I relied on electricity in nearly everything I did in my day-to-day life. Without power, I watched the snow fall and took in the sights and sounds of Chama and the surrounding the area. Due to the lack of electricity, I couldn’t remain plugged in so I had to stop and smell the roses. I enjoyed the brief respite from the usual incessant onslaught of so-called modern day conveniences. All-in-all, the events of the day made for a very memorable one that was highlighted by equally memorable photos.

This picture was taken at Lake Tahoe on a calm day. If you look closely at the photo, you can see small waves starting to form in the reflections of the trees. When I took the photo, I was drawn to the V-shaped wake from the kayak. In a matter of moments, the wind started to pick up and the surface of the lake went from almost glass-like to choppy and tossed. The kayaker was safely ashore as the winds grew stronger and stronger. While the light wasn’t quite right when I took this photo, capturing the kayak’s wake, with the individual paddle strokes clearly visible, was worth the effort. When this opportunity came along, I was concentrating on photographing birds that were perched high in an old, dead tree. When one of them flew to a new location, my eyes swept across the scene captured in the photo. I only had enough time to change the camera from shutter to aperture priority before I took this photo. I used a high f-stop to enhance the photo’s depth-of-field. A few seconds later, the photo had changed completely. At the time, I didn’t realize how lucky I had gotten when I pressed the shutter release. Only when I saw the picture on my monitor did I come to appreciate fully the clarity of the details in the photo. This picture tells a story and provides the context for it in a spectacular setting. What it doesn’t tell is that within a few hours, a cold front swept through the high Sierra and dropped several inches of fresh snow.

I heard a bird pecking (hammering, actually) at the trees, but I couldn’t locate him. I craned my neck and tried to find him, but to no avail. I listened and finally located him high up in a tree. But, when I saw him, he saw me. An instant later, he disappeared. Then he’d start pecking on another tree. I’d walk toward the sound to try to find him again and he’d fly to another tree. The new spring foilage made my search for him all the more difficult as he had literally millions of fresh, green leaves to hide behind. Despite his constant pecking, he proved himself to be quite adept at maintaining his privacy. Our impromtu game of hide-and-seek continued for a while until he stopped pecking and I tired of the chase. Without any sound to give away his position, my chances of finding him plummeted. I was about to give up when I took one more scan of the trees based on his last known location. I saw movement and there he was! To say that I got lucky is an understatement of the highest order. I saw him walking up the side of a tree as he listened for his quarry. He was so engrossed in tracking down his breakfast, he didn’t hear me approach or see me watching him. Even when I pressed the shutter release, he remained fixated on the task at hand. His efforts paid off when he found something to eat. In this photo, you can see a tiny insect morsel in his beak. I don’t know what it was, but he left the tree shortly after this photo was taken. He began pecking on another tree a few moments later. However, unlike what I had done previously, this time, I left him to enjoy his meal and to continue his adventure without my interference. I knew that it would take a while for my neck to recover from constantly looking into the tree canopy to find him. But, I think the photo was worth the effort, including my sore neck. A couple of aspirin later and I was nearly as good as new!

This photo was taken in the early morning on a very cloudy day. I arrived at the location before sunrise and waited until there was enough light to take photos. The bird was very skittish and didn’t stay in one place too long. I used a long lens and was able to capture the shot as he flew to a location further away from me. Because of the constant movement of the animals I wanted to photograph, I didn’t use a tripod so that I could point my camera more quickly and easily in my attempts to get the shot. I used a high ISO and fast shutter speed to freeze the bird in flight. Shortly after this photo was taken, the bird decided that he’d had enough of the stranger with the camera gear and flew away.

Colorado River at the Bottom of the Grand Canyon

Colorado River at the Bottom of the Grand Canyon

Trying to do justice with any photo of the Grand Canyon is one of the hardest things I’ve ever attempted with a camera. Due to the overwhelming size and sheer vastness of the canyon, a single photo cannot capture everything there is to see or even the iconic essence of this amazing canyon. The Colorado River flows 277 miles through Grand Canyon National Park, the average width of the canyon is 10 miles, the average depth is 1 mile, and the average width of the Colorado River in the park is 300 feet or the length of a football field without the end zones. The canyon was carved over roughly 6,000,000 (6 million) years as the Colorado River cut through the uplifted Colorado Plateau. The exposed geological strata in the canyon reveal roughly 2,000,000,000 (2 billion) years of the geological record. Grand Canyon National Park is just over 1,217,403 acres or 1,904 square miles in size. It is a little over 23% larger than the state of Rhode Island. From this picture, the size of the canyon is put into some perspective when you remember that, on average, the river at the bottom is 100 yards wide. To take these photos, I got to the canyon before sunrise and took as many images as I could as night gave way to dawn. Every moment brought about a change in the amazing colors of the canyon. While I was there, the striking hues and shadows in the landscape literally morphed and changed before my eyes as the sun climbed higher and higher into the eastern sky. The temperature was in the low 30s and the smart people were either still asleep or savoring a cup of hot coffee.

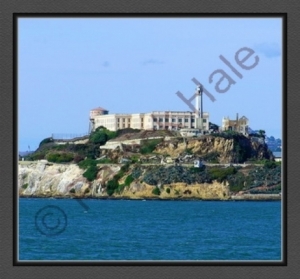

Alcatraz Island is located roughly 1.5 miles offshore in San Francisco Bay. Known colloquially as The Rock or Traz, it served as a federal prison until 1963. The first explorer to document the island was Juan Manuel de Ayala in 1775 as part of his charting San Francisco Bay. He called the island “La Isla de los Alcatraces,” which translates as “The Island of the Pelicans.” In 1827, French Captain Auguste Bernard Dehaut-Cilly noted that the pelicans were so numerous on the island as to be innumerable and that when a gun was fired over their heads, they took to flight “in a great cloud with a noise like a hurricane.” Today, the California Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus), the bird which gave the island its name, no longer inhabits The Rock. Alcatraz is now operated by the National Park Service and is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. When this picture was taken, the temperature was in the high 40s with a very strong wind. While the waves in San Francisco Bay were not high, the swells were deep and frequent. The sun may have been shining, but it provided little warmth to those who ventured out. The Rock serves as a clear and stark reminder of a by-gone era.

SS Jeremiah O’Brien Liberty Ship

SS Jeremiah O’Brien Liberty Ship

I took this picture because of what the ship represents in the history of the United States and of the world. (If you look closely, you can see the iconic Golden Gate Bridge in the background.) Thin clouds and an incessant, gusting wind marked the clear, cool day. I didn’t use a tripod and compensated for camera movement due to the blustery winds by using a high shutter speed. The SS Jeremiah O’Brien represents an entire class of ships that were needed as part of the war effort during WW II. From 1941 to 1945, 18 American shipyards produced 2,751 Liberty Ships making this the most widely and numerously produced ship of a single class. The official designation for the ship’s class was EC2-S-C1. (EC for Emergency Cargo, 2 for a ship between 400 and 450 feet in length, S for Steam engines, and C1 for Design C1. One of the most remarkable aspects of the Liberty Ships was that they had a design-life of only five years. Liberty Ships sailed on well after the end of World War II. The first Liberty Ship launched was the SS Patrick Henry on 27 September, 1941. In his remarks at the launching, President Franklin D Roosevelt cited Patrick Henry’s 1775 “. . .give me liberty or give me death!” speech and said that the ships of this class “would bring liberty to Europe.” That reference gave rise to the common name of Liberty Ships. Some naval historians have noted that the sheer number of Liberty Ships produced and put into action simply overwhelmed the German Navy’s ability to sink them with its U-boats. By the end of the war, building a Liberty Ship took, on average, just 42 days from laying the keel to putting out to sea. They displaced roughly 14,500 tons, had a top speed of (allegedly) 11 knots, and a crew of 41. There is no doubt that Liberty Ships played a key role in turning the tide against totalitarianism in World Word II. Millions of people around the world today enjoy the sweet taste of liberty and fruits of freedom due to this class of ship and the crews who, despite horrific losses in men and material, continued to sail unarmed, slow cargo ships into harm’s way.